The trees are coming into leaf, the fields here in North Yorkshire are full of lambs, and the lone peacock’s loud and mournful cries may be heard as he fruitlessly wanders the grounds of Peel’s base on the Broughton Hall Estate. He is hoping to find a mate. Sadly there isn’t one.

All this Spring going on can only mean one thing for Simulated Patients – it will soon be Exam Time for student doctors.

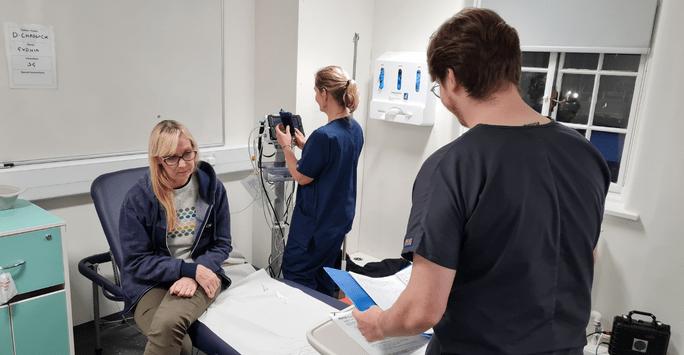

As well as written exams, medical students have to take annual practical exams called OSCEs, which stands for Objective Structured Clinical Examination. They move round a series of little booths, called “stations” and have to do a different task in each station.

In the early days of OSCEs in the 1990s (a lot of our team remember those days!) it was believed that the more stations there were, the more accurate the result would be. So the poor students had to undergo about twenty different stations during the course of a morning and would emerge looking both exhausted and traumatised.

Fortunately, after a few years, research indicated that about eight stations was enough to give a reliable result in most circumstances, so OSCEs don’t take as long these days.

They still, however, require a huge amount of organisation and commitment from all those involved.

Usually, at least two or three of the stations require a Simulated Patient (who are usually, though not always, a trained actor) so the students can be assessed on taking the medical history from a patient, or explaining a procedure, or even breaking bad news. Because medical schools often have several hundred students in a year group, the eight stations need to be repeated lots of times in “circuits” – each circuit has the same number of stations.

This means that, if there are, say, three Simulated Patient stations in a circuit, and fifteen circuits, then you need forty-five Simulated Patients, and generally a couple of “spares” for each role in case anyone’s ill. So on any one day, you might need, for example, seventeen young women in their twenties, seventeen men in their sixties, seventeen women in their fifties.

The OSCES – especially the final-year OSCE at the end of the students’ training – are high-stakes exams and it’s therefore crucial that every student is offered the same opportunity.

Each station has a “brief” for the Simulated Patient with lots of detail about their symptoms, family history, medication history and anything else that’s needed for the role, and the Simulated Patients have to learn these with total accuracy.

There is sometimes a session to standardise the way the Simulated Patients are going to play the role. I’m delighted to say that our large PEEL cohort of Simulated Patients are totally dedicated to getting it right! Although the doctors – it’s generally doctors – who write the briefs have always put in a tremendous amount of work on them, there are always a few key questions that arise. “It says I share a bottle of wine with my husband – is that equal shares or is one of us downing two-thirds of it?” “It says that the back pain started three weeks ago when gardening – have I ever had it previously?” These may seem like trivial details but it really matters when it comes to giving each student the same chance for success; it is very easy to get distracted by red herrings if briefs are not properly scrutinised and SPs not standardised.

It is also vital to get the emotional level right. It’s no good having a “depression” scenario if one person playing the role sounds suicidal and another sounds just a little bit miserable. We practice again on the morning of the exam, to make sure all the Simulated Patients start at the same emotional level.

Often there’s an opening line which is either written into the brief or decided at the training session – this is to make sure that every student is offered the same start to the task. For undergraduates it’s usually fairly straightforward “I’ve been getting a lot of headaches recently” or “I keep getting indigestion”. For postgraduates, however, these can be much more challenging to reflect the tricky situations that doctors may come across either in hospital or in a GP surgery. My favourite opening line of the many roles I’ve played over the years, was in an exam for qualified doctors. “You will tell my ex-husband it’s all his fault, won’t you?”

All this careful standardisation really pays off on the days of the exams. When I am Simulated Patient Co-ordinator for the day, I stand outside the different stations, listening to each person who is playing the same role. Of course, every student is different so each scenario may proceed differently depending upon the student’s reaction and the questions asked: but it’s great when I listen in and it sounds as though it’s the same patient in each booth.

Bring on OSCE season! I’m looking forward to it.

By Daphne Franks, Training & Development at Peel Roleplay